With another Arts competition approaching it was time to determine what my theme would be. During this last year I have drawn marginalia on pottery for various fundraiser events and gifts and with each new cup drawn interest in the cups seems to grow. This has led me to research more and more marginalia and finally leading me to drawing a cup we call in my house “Attack on Bunny Castle”. The cup is based upon a piece of marginalia from the Breviaire of Renaud de Bar folio 137.

This cup quickly became my husband’s favorite cup and from it spawned more research on these attacking bunnies. Once I started to look I found them everywhere, each one more strange or fierce then the last, and so the idea of creating a set up cups based on bunny/rabbit marginalia was decided. Talking with my Peer she recommended to take the project one step further and look not only at what was there, but why were these particular animals used. This put the project down a deeper rabbit hole (first time I have gotten to use that phrase regarding the actual animal). Several interlibrary loan books, websites, magazines, and museum sites later I found at least the start of the layered meaning of these small furry critters.

Source of images

While there are many examples of rabbits found in various manuscripts while researching examples, many manuscripts from the 12th century and beyond proved to contain the best examples. This rise in representation coincided with a society fad of the time. Rabbits were imported into Western Europe in the twelfth century. The aristocracy would build warrens which would allow the rabbits to multiply and provide fruitful grounds for hunting (Heck 41). As the popularity of warrens and the keeping of rabbits grew, their presence in manuscripts also grew.

An example here or there can be found in various books, but during my research I came across several images that all linked back to the same set of books, those commissioned for or by (there is some uncertainty) Renaud de Bar.

Renaud de Bar was the son of Thibaut II, Count of Bar, and Jeanne de Chatillon-Toucy. He became the bishop of Mentz in 1303. As part of his elevation to bishop there were two books commissioned including a Pontifical and Breviary. As member of the Lorraine nobility, Renaud would have likely participated in hunting for sport. If he did not own his own rabbit warren it was likely that access could be found through one of his family of connections (“The Pontifical of Renaud De Bar”). Whether it was his ties to hunting or the link of bunnies to nobility of the time, dozens of examples of rabbits can be found gracing the pages of his books, and it is from these pages that my examples were chosen.

Rabbits proved to be a rich example of the polysemic nature of images found in marginalia. For the exhibit I choose several examples which highlight some of the varied meaning behind this simple little animal.

Sexual Pursuit/Lust

One usage of rabbit is that of a sexual interpretation. The Latin name for the rabbit (conil) was widely understood to be a metaphor for the female sexual organ due to its similar sounding name (Heck 41).

The image in the Breviaire found on Folio 352 shows a man embracing a hare or rabbit. The man is half dressed as his legs are bare. The text on that page discusses Girding one’s loins and curbing the excess of the flesh (Davenport, Kay) further leading credence to this interpretation.

Hunting / Pursuit

Hunting for sport was a popular past time for those of means in the Middle Ages. Packs of dogs were raised and prized by their owners and various animals were raised to hunt. One such hunted animal was the rabbit.

These hunting scenes may also have additional meanings. The dog is often a symbol of devotion, but also of depravity and foolishness, and representing man. Using this interpretation chase scene between the dog and the rabbit as shown below may be seen as one of a male suitor pursuing the fleeing female (Heck 284).

Rabbit used as goods

Rabbit fur was widely used as trim and lining for items such as gloves and hoods. It not only insulated the items, but the soft feel and look provided a bit of elegance to these items. Several marginalia showcase the conflict between the tailor and the rabbit playout through the texts. The example chosen shows the tailor with his sheers approaching a mother rabbit and her babies.

Battle of Nature or of the Sexes

Continuing with the theme of dogs representing male figures and rabbits female figures there are several images which could represent the battle of two animals as their human counter parts due to the use of weapons and tools. The conflict between these two could be symbols of the battle of or between the sexes, or they could represent the battle between the predator and its prey that plays out in nature.

Depicting Scenes from the text

The text in the Breviaire folio 263 references the story of Saint Lucy. The story recounts that “Lucy, the venerable virgin of Syracuse parents, most noble, with her mother, Euticia often visited the sepulchre of the blessed Agnes in veneration”. The man in the scene may represent the poor (note lack of leg coverings) whom Lucy gave her inheritance to (Davenport, Kay).

In Folio 298 of the Breviaire the text ‘Bishop Pau, confessor of the Lord, strengthens by your holy intercession the people of your diocese’ above the image of a Snail man dressed as a bishop (as noted by the hat) who is being addressed by a rabbit/hare dressed in a robe. Imagery could be loosely related to the text.

Reference to well known stories/parables

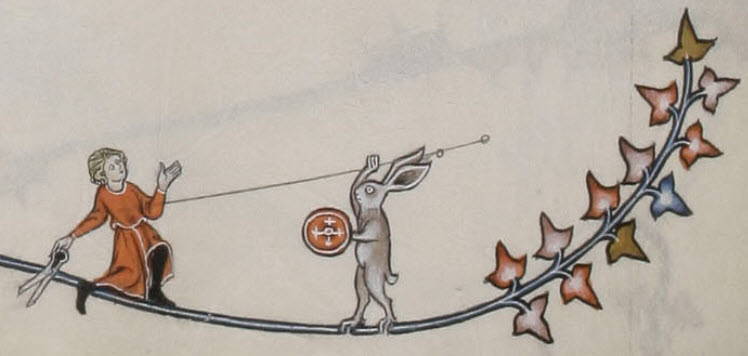

While not specifically mentioned in a text marginalia would be drawn in such a way as to reference back to a common or well-known story or theme which could be easily identified. One example in these texts is the David vs Goliath theme found in the rabbit vs knight. The difference in size as well as the usage of the sling and crook further confirm this theme.

World turned upside down

A common theme in marginalia is that of the world turned upside down. In this strange world the natural order of things is reversed, and the grotesque items come out. Hunters now become the hunted, strange beasts roam free, and all is not normal in the world. There are several such images in these and various other texts.

My Pottery representation of Marginalia

Final Thoughts

While I knew that the images in the marginalia were for entertainment purposes and could mean something, the number of meanings to each item was truly staggering. Not only the figure in the image could have various meanings their color, clothing, and even posture could mean something different. Like with many pieces where the original artist is not around these images leave themselves open for interpretation and different people can claim that they represent different items, and there is no way to know for certain what was ment. As with most works of art I wonder what the creator would think of the ideas being presented about their works.

Bunnies are not an end of the journey for marginalia research. There are many more animals out there with various meaning and various situations in books waiting to be found and researched.

Sources

“Breviary, (‘The Breviary of Renaud De Bar’ or ‘The Breviary of Marguerite De Bar’).” Detailed Record for Yates Thompson 8, The British Library, 25 Aug. 2005, https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=yates_thompson_ms_8_fs001r.

“ Bréviaire De Renaud De Bar.” Initiale, Institut De Recherche Et D’histoire Des Textes Du Centre National De La Recherche Scientifique, http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/codex/5035.

Conde, Musee. “Folios 3v-4.” Histoire D’amour sans Paroles, 1500.

Davenport, Kay. The Bar Books: Manuscripts Illuminated for Renaud De Bar, Bishop of Metz (1303-1316). Brepols, 2017.

Heck, Christian, et al. The Grand Medieval Bestiary: Animals in Illuminated Manuscripts. Abbeville Press, 2018.

“The Pontifical of Renaud De Bar.” The Pontifical of Renaud De Bar | ILLUMINATED, Fitz Museum, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/manuscript/discover/the-pontifical-of-renaud-de-bar/section/owner.